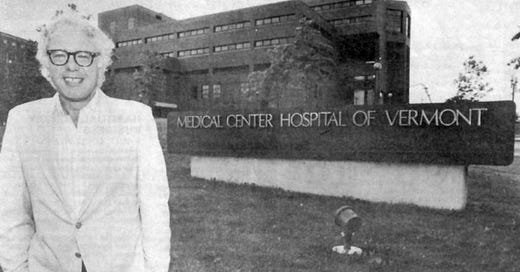

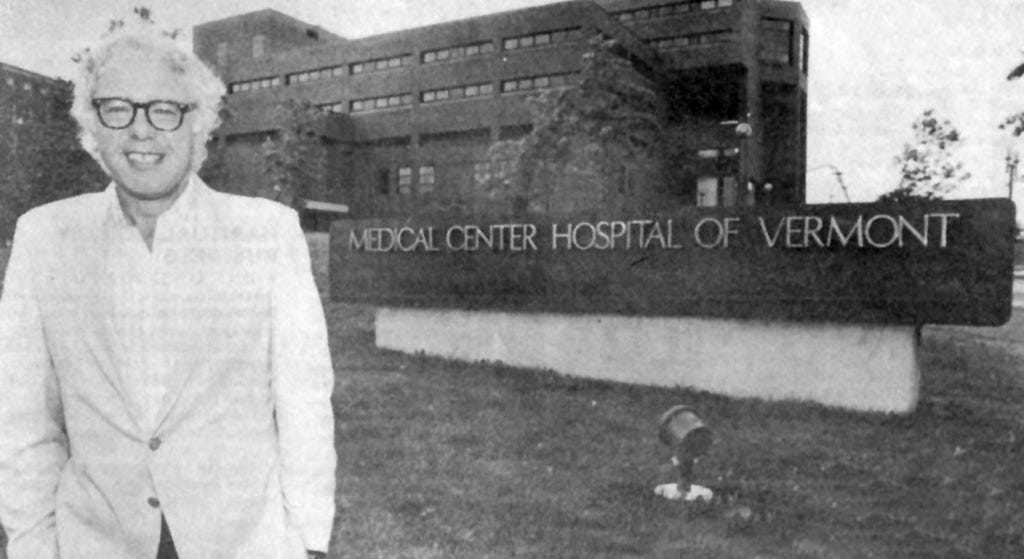

I love Bernie Sanders and am therefore wildly proud that I was a very early constituent of his, thanks to the accident of having been born in Burlington, Vermont in 1986 when Bernie was mayor. While I wish I could also say that this means I’ve known about him my entire life, my family left Vermont before I turned four so I really only found out about Bernie when the rest of the country did, which is to say when he threw his hat in the ring for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination and every American leftist with a brain not completely destroyed by academia or sectarianism was like, “Yeah, why not.”

Leftists love going on about what “radicalized” them. This is ostensibly meant to describe the process by which the scales fall from one’s eyes and one goes from a garden variety liberal to a person who reads Antonio Negri or believes in the labor theory of value or develops the urge to throw molotov cocktails.1 I like to think, though, that Bernie deradicalized me. What I mean is that before his 2016 run, the American left was so weak and so disconnected from any kind of power that it was easy and satisfying to take the most radical or maximally-left positions on any given topic, in the absence of any real political leverage. In the years between Occupy Wall Street and Bernie’s first campaign, my friends and I spent our time holding miserable reading groups on arcane academic texts and saying things like FULL COMMUNISM NOW and ABOLISH WORK and going willingly to Left Forum. We felt militant and pious musing about armed insurrection or fetishizing marginality—the more “marginalized” a group or identity or belief was, the more you had to fixate on it, obviously—and the fact that none of this went anywhere was just further confirmation of how righteous it was, because anything that the general public found agreeable had clearly already been corrupted by capitalism.

Whether we understood it at the time or not (and we largely didn’t; we were in our twenties and therefore idiots), this preoccupation with an abstract “radicalism” was just a type of subcultural nihilism born out of decades of left-wing defeat. Forty years of neoliberalism and the bipartisan smashing of organized labor had confined the left to niche activist spaces and the academy, where politics was little more than a thought exercise and the stakes were low to nonexistent. People in these circles pontificated constantly about how society needed to “reimagine” various institutions and ideas—the police, the family, money, gender, health, sexuality, beauty, and so forth—as though the primary impediment to a more egalitarian order was that people just hadn’t thought hard enough about what that order might look like. Everyone loved the line that it was easier to imagine the end of the world than it was to imagine the end of capitalism, but in retrospect, I don’t think leftists prior to Bernie actually had much trouble imagining the end of capitalism. They just had thoroughly useless ideas about how to get there.

The astonishing popularity of the two Bernie Sanders campaigns suggested that the fundamental problem with the polity wasn’t a lack of imagination, but a lack of organization. More than any radical text on post-work futures or the abolition of prisons or a society without cops or bosses, Bernie’s simple, straightforward, and frankly unimaginative program punctured the fog of twenty-first century capitalist realism. (Here a leftist might grouse that the Bernie platform was still capitalism or just social democracy, and while that’s technically true, it’s also beside the point: If you’re scoffing at social democracy as though we’re in any danger of social democracy seducing the population into complacency in a country that can’t even seem to sustain a permanent expanded child tax credit, I’m sorry to say that you have not yet gotten a grip.)2 Running as a self-described democratic socialist on a left-labor platform, Bernie received more than 13 million votes in 2016—winning 23 states in a primary race he had entered with virtually zero name recognition—and, four years later, won California, the most populous state in the US. As Matt Karp put it in 2020:

Bernie lost. But over five years, he gave the feeble American Left a precious gift: a common program, based on ambitious, universal economic demands—Medicare For All, college for all, jobs for all—and a common politics, based on a fierce rejection of billionaire class rule. These are things the US Left has never had before in this century, not after the Battle in Seattle in '99, not after the crash in '08, not after Occupy in '11 or Ferguson in '14. Bernie's program and Bernie's politics showed that a Left of thousands can become a Left of millions.

Bernie, in other words, demonstrated that it was possible and desirable to forge a politics around a left-wing vision of society that was majoritarian rather than vanguardist; that the fight to remake the government and the economy in the interests of the working class instead of the rich was a project that didn’t, in fact, first require the “radicalization” of ordinary people in the way that so many leftists had previously insisted. After all, as Bernie himself said over and over on the stump, “These ideas are not radical.”

—Adapted from a 2021 Jacobin Show segment

It also, unfortunately, kind of just makes it sound like you joined al Qaeda

“In the short term we’re all social democrats” –Vivek Chibber

The trouble is that the commie take on Bernie - that he would ultimately prove to have his biggest impact in pushing left wing voters to vote for Democrats, rather than in "pushing Democrats left" - has proven to be indisputably true. The sheepdog allegations may not be kind or useful, but they are simply factually correct.

A lot of people would rather keep on their performative activism and self-victimization than read something like this, and it hurts.